In a distributed application, we always have to consider the impact of faults and solutions of how we can solve it while balancing the cost, response time and other performances.

Type of Failures

First of all, let’s have a look at what type of faults do have.

- Omission failures

The server fails to respond/receive to incoming requests and fail to send messages - Timing failures

The server fails to respond within a certain time - Response failures

The server might response incorrect - Arbitrary (byzantine) failures

A component produces output it should have never produced (may not be detected as incorrect): arbitrary response at arbitrary times - Crash

Server halts!

Fault-Tolerance

Usually, we use redundancy to do failure masking, in this article, I will introduce 3 types of redundancy of how and when to use each one.

First, consider the two-generals' problem, where we have two armies, each led by a general, are preparing to attack a village. The armies are outside the village, each on its own hill. The generals can communicate only by sending messengers passing through the valley. As the way they communicate might fail, we have to add the following redundancy to ensure the attack is ontime.

Physical Redundancy

As the name “Physical” says, we have to add physical devices to allow some failures on some devices. In the two-generals' problem, there’s a restriction in the problem that there’s only two armies so we could implement physical redundancy, however if we want to make sure the attack, we could add more attacking armies to allow some sending messengers failed to send messages.

Time Redundancy

We could let armies send messengers multiple times to allow some of them fails, and in other situation, time redundancy means to repeat actions multiple times. But for this type of redundancy, we have to consider the costs of excuting each actions.

Information Redundancy

Another method of tolerating this error is to send extra messengers to other armies to increase success rate, in other type of problems, we send extra bits instead.

Triple Modular Redundancy

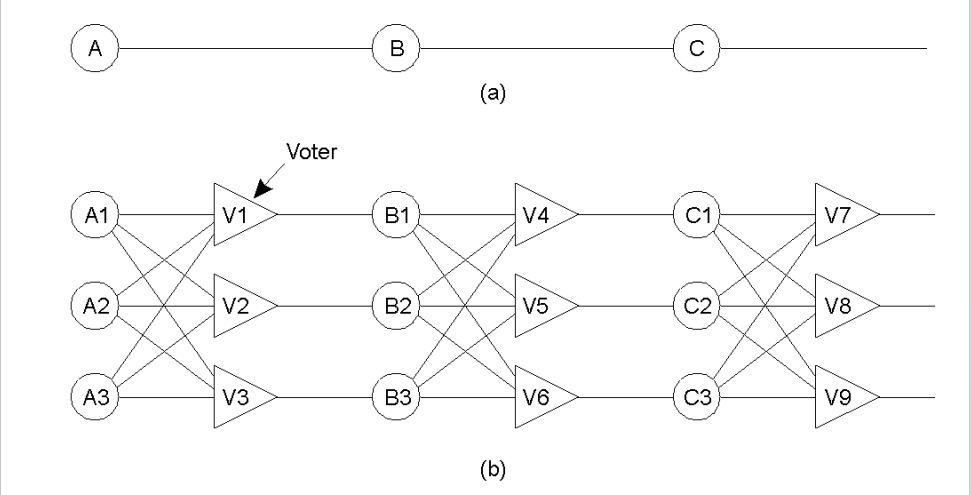

The above picture is a redundancy model, and an example of physical redundancy. It contains three components executing the same functions, all of them run in the same time and getting their own outputs. Afterwards, there is a voting mechanism, which compares and select the result with most components producing. This means even if one of component producing a wrong result or having a fault, the rest of the system could still work perfectly.

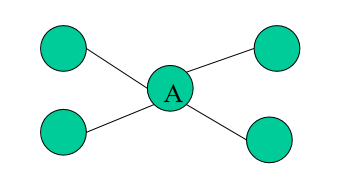

Single point of failure

Single point of failure means a failure could cause the fault of the whole system. Consider the graph below, the central point’s fault would make the whole system lose connection.

The triple modular redundancy is a model avoid this kind of failure, we have to avoid it in the real system design.

The triple modular redundancy is a model avoid this kind of failure, we have to avoid it in the real system design.

Replications and Performance

While considering adding redundancies to the system, how to manage the effect of redundancies to the performance become a important problem. As adding information redundancy, we will have more data replications, this results in increased communication costs between processes and the medium on which the data is stored. An useful method of saving costs is to place copies of data in the proximity of processes, the time to access data decreases in this case, and it is also good for achieving scalability.

Another problem brought by maintaining replicas is the consistency problem. If one of the replica is being modified, the rest of the replicas will required to be modified, too. Moreover, during the update, other processes couldn’t access the data, which waste a large amount of time (However some system do need it). We could also loosen the consistency constraints - not all copies need to always be same everywhere. These two ideas bring us two consistency protocols:

Strict consistency

Any read to a shared data item x returns the value stored by the most recent write operation on x. In a distributed system, this requires us to have an accurate global times.

Eventual consistency

Given a sufficiently long period of time over which no changes are sent, all updates are expected to propagate, and eventually all replicas will be consistent.

Availability

The availability is a value measures the probability a replicated service is able to use. A equation could be:

- 1 - p(all replicas have failed)

- p(all replicas have failed) = p(replica 1 failed) * p(replica 2 failed) * … * p(replica n failed)

- p(replica n failed) = $\frac{t}{f+t}$ (t is the mean time to repair a failure, f is the mean time between failures)